One of the most basic, yet most effective, means of reducing our odds of death by auto traffic is to reduce our exposure to said traffic. I’ve written about this before, in terms of how we can double our driving safety by cutting our annual mileage in half. However, the information bears repeating, given the fact that we drive more, on average, in the United States than in any other country on the planet.

I find it helps to have international frames of reference when discussing driver safety, as it often provides us with a greater perspective of how things we take for granted in the US might not necessarily be the safest or even most practical ways of doing things. Today’s article will explore US driving rates across ages and compare them to a number of countries with a focus on Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. We’ll then extrapolate what death rates in each country would look like if each nation adopted the other’s driving habits.

Just how much do Americans drive per year, on average?

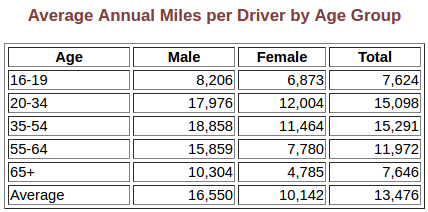

According to the Federal Highway Administration, Americans drive 13,476 miles per year on average. These figures vary significantly by age and gender, with men driving more than women at all stages of life. The peak driving ages for both genders occur between 35 and 54 for men, with an average just beneath 19,000 miles, and and between 20 and 34 for women, with an average of just over 12,000 miles. On average, then, the typical American drives a shade under 37 miles a day.

Per the IIHS, 35,092 Americans died from auto traffic in 2015, making it the worst year since 2008, where more than 37,000 died. The per capita death rate was 10.9 auto deaths per 100,000 residents, while the death rate per 100 million miles driven was 1.12.

Let’s look at how this compares to the average Norwegian, Swede, and Englishman or woman.

How many miles do Norwegians drive on average?

Per Statistisk Sentralbyra, or Statistics Norway, Norwegians drove an average of 12,289 km in 2015, or 7,636 miles per year. This translates to an average of 21 miles a day, or about 57% of the average US daily mileage.

Per SSB, 117 Norwegians died from auto traffic in 2015, making it the best year since 1948. I’ve written before about how Norway compares very favorably to the United States in auto safety, whether in overall fatalities or in child safety, and this was underscored in 2015. The per capita death rate was 2.2 auto deaths per 100,000 residents, which was one of the lowest in the world.

The 2016 IRTAD road safety report notes the peak fatality figures were reached in 1970 with 560 deaths. The report credits the dramatic drops in death rates since the 70s to a variety of causes, including safer cars, reduced speed limits, introductions of median barriers, and seat belt campaigns, as well as an overall Vision Zero strategy.

How many miles do Swedes drive on average?

Per Transport Analysis, Swedes drove an average of 12,216 km in 2015, or 7,591 miles per year. This translates to an average of just under 21 miles a day, or about 57% of the average US daily mileage.

Per Transport Analysis, 259 Swedes died from auto traffic in 2015. The 2016 IRTAD road safety report notes the peak fatality figures were reached in 1965 and 1966 with 1,313 deaths, and 2015’s figure appears to be Sweden’s lowest in modern history. The report credits the dramatic drops in death rates since the 60s to “safer cars, lower speeds, and the introduction of median barriers” – all elements of Vision Zero.

As with Norway, I’ve written about how Sweden experiences very few deaths, proportionally speaking, to the US, both in terms of overall deaths or in child safety (this is where extended rear-facing was born). In 2015, the per capita death rate was 2.7 auto deaths per 100,000, also one of the lowest in the world.

How many miles do UK citizens drive on average?

Per the UK Government’s Road Use Statistics 2016, the British drove an average of 6,488 miles in what appears to be 2013. This translates to an average of just under 18 miles a day, or about 49% of the average US daily mileage.

Per National Statistics, 1,732 Britons died from auto traffic in 2015, which appears to be the second best year in modern history after 2013, when 1713 died. This figure also represented a 46% drop in 10 years compared to the 3,201 death toll in 2005. The 2016 IRTAD road safety report notes the peak fatality figures were reached in 1941 with 9,000 deaths. In 2015, the per capita death rate was 2.7 auto deaths per 100,000, again one of the lowest in the world.

Interestingly, Sweden and the UK shared the same per capita death rate, indicating that the difference in total road deaths between the two countries could be entirely explained in 2015 due to the difference in total population between the two countries. There were approximately 6 Brits for every Swede, so with an identical death rate, the death toll was 6x higher in the UK than in Sweden.

How do the average miles driven by Americans affect our annual road death toll?

We’ve established that Americans drive more miles per day (and by extension, per year) than Norwegians, Swedes, and Britons, on average. However, the next step in figuring out how our driving patterns–or more specifically, the extent of our driving–affect our annual road death toll. To put the numbers into focus, let’s compare each of the three countries to the US.

If Americans drove as few miles as Norwegians or Swedes (i.e., 21 miles a day, or 57% of 37 miles a day), instead of 35,092 deaths in 2015, we’d have had approximately 20,002 deaths, representing 15,090 lives saved.

If Americans drove as few miles as the British (i.e., 18 miles a day, or 49% of 37 miles a day), instead of 35,092 deaths in 2015, we’d have had approximately 17,195 deaths, representing 17,897 lives saved.

That’s huge.

How would the annual fatality rate in the US change if the per capita death rate were the same as those in Norway, Sweden, or the UK?

Now that we’ve compared how many fewer road deaths the US would suffer annually if we reduced our driving rates to those found in Norway, Sweden, and the UK, let’s compare how the annual fatality rate would change if we shared per capita rates with those countries. This figure is particularly interesting when combined with the changes based on mileage, as the closer the road death toll from a modified per capita rate is to the road death toll from a modified mileage, the more our mileage (i.e., amount of driving) explains our per capita rate.

To put it simply, if adopting the per capita death rates of other countries wouldn’t give us significantly different annual death tolls than if we simply adopted other countries’ driving frequencies, this suggests the primary problem in the US with respect to road safety is simply how much we’re driving. On the other hand, if the modified road death toll from a modified per capita rate isn’t close to that of a modified road death toll from a modified driving rate, it suggests the US’ road safety issues are primarily due to other factors (e.g., the safety of the road network or the safety of our vehicles). The availability of other transportation options (e.g., buses and trains) also counts as a separate factor that could explain the difference in safety. Let’s see.

If the US shared Norway’s per capita death rate (2.2 instead of 10.9 deaths per 100,000 citizens), instead of 35,092 deaths in 2015, we’d have had approximately 7,083 deaths, representing 28,009 lives saved.

Which matters more? Reducing driving rates or the overall per capita death rate?

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can buy my books here or do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.

If you find my information on best practices in car and car seat safety helpful, you can buy my books here or do your shopping through this Amazon link. Canadians can shop here for Canadian purchases. Have a question or want to discuss best practices? Send me an email at carcrashdetective [at] gmail [dot] com.